According to a recent article from The Fiscal Times, writer Yuval Rosenberg notes the peculiar dichotomy between the rapid rise in employment figures and the inert sentiment amongst millions of workers, many of whom struggle to make ends meet in this supposedly rejuvenated economy. The tick up in the unemployment rate to 5.7-percent last January hardly seems to capture the real condition of middle-class America, which has been proven by many sources to suffer wage stagnation.

Unemployment Rate A Big Lie?

Pushing criticism further, the chairman and chief executive officer of Gallup, the venerable polling organization, proclaimed that employment trajectory data is a “big lie” perpetuated by the government and big business. “’Right now, we’re hearing much celebrating from the media, the White House and Wall Street about how unemployment is ‘down’ to 5.6 percent,’ Gallup’s Jim Clifton wrote in an attention-grabbing opinion piece published Tuesday on the polling firm’s site. ‘The cheerleading for this number is deafening. The media loves a comeback story, the White House wants to score political points and Wall Street would like you to stay in the market’ (Rosenberg, Yuval. Is the Unemployment Rate of 5.7 Percent Just a ‘Big Lie’?. The Fiscal Times. February 6, 2015. Web.).”

As confirmation of this “lie,” many economists and financial experts will point towards the oft-cited accusation that job-seekers who become discouraged in their search for employment are no longer counted as “unemployed” by the U.S. Department of Labor. Laid-off employees whose unemployment benefits have run out also receive this dubious upgrade. Yet as valid as this context may be, it’s very much low-hanging fruit, one that could easily be countered with a different context.

In order to gain a full understanding of employment, we must quantify the issue. The reason why the government is so easily able to proclaim a recovery in the labor market is because it’s true. Since the global financial collapse of 2008, more jobs have been added to the domestic economy on a nominal basis for all sectors and industries. That being said, the government’s claim is based on a simple linear regression of employment data; essentially, the recovery is a non-weighted average of extreme highs, lows, and everything in between. Under that algebraic standard, it is inherently obvious that employment figures will rise. There are simply more good days than bad days, to be elementary.

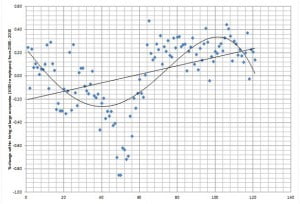

The real issue is the non-linear trend. Employing a fourth-degree polynomial regression against the rate of change of hiring at large companies (1000+ employees) between the years 2005 to January 2015, it’s quite clear that the velocity of hiring peaked in 2013 before settling back down to its standard deviation. This is in sharp contrast to the aforementioned linear trend, or the basic average of employment data, which is projecting positively.

Another concept that is not mentioned by the government is that negative outliers, or months when changes in employment figures are particularly low, are occurring with more frequency than positive outliers. In fact, since the unofficial recovery from the 2008 collapse (around the second quarter of 2010), negative outliers have increased in terms of velocity. This means that while politicians can celebrate months of extremely positive data, there are more instances of extremely negative data to counteract the euphoria.

While the Department of Labor is not overtly manipulating employment numbers, they are guilty of using both a contextually inaccurate framework and a technical methodology that is woefully inadequate in providing an unbiased analysis.